In the field of natural history a Lazarus species is one thought to be extinct which then seemingly comes back from the dead.

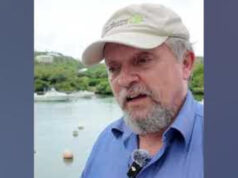

And wildlife ecologist Mark Outerbridge has recently recounted his role in the rediscovery of one such endemic Bermuda animal.

“I have had the privilege of being involved with one of the most gratifying stories of conservation in Bermuda’s history,” he writes in the most recent edition of the Department of Environment & Natural Resources newsletter Envirotalk. “It includes drama, serendipitous discovery, international collaboration, hard work and no small amount of luck.”

Tongue only slightly in cheek, Bermudian researcher Mr. Outerbridge goes on to say the story actually begins a million or so years ago: that’s when the Gulf Stream carried a colony of North American land snails to the island on driftwood or vegetation.

“The descendants of those remarkably lucky snails then spent hundreds of thousands of years living here and [evolved] into at least 12 different species within a single genus known as Poecilozonites [pronounced po-sill-oh-zone-eye-tees],” he continues. “This genus is entirely unique to Bermuda and each species exhibited its own particular size, shape and colouration — all of which is richly described in our fossil record”

The largest of these snail species was reported to reach 46 millimetres in shell diameter; the smallest only five millimetres.

At least three of the Poecilozonites are known to have survived into the 20th century: Poecilozonites bermudensis, or the greater Bermuda land snail; Poecilozonites circumfirmatus, or the lesser Bermuda land snail; and Poecilozonites reinianus, a small snail found only from Bailey’s Bay to Shark Hole and last seen in the wild in 1924/1925.

The greater Bermuda land snail’s territory was gradually reduced to just two known locations, one in St. George’s, the other in Hamilton Parish; it was thought to have become extinct by the early 1990s.

“The lesser Bermuda land snail appeared to have fared slightly better; a summer student for the Department of Conservation Services, Alex Lines, confirmed live snails at four coastal locations in Smith’s, Devonshire and Paget Parishes in 2002,” says Mr. Outerbridge. “Wolfgang Sterrer, curator of the Natural History Museum at the time, very wisely collected specimens and sent them to the London Zoo for safekeeping.”

“Since then we fear that this species quietly went extinct in the wild.”

Flash forward just over a decade.

In the summer of 2014 Mr. Outerbridge received a visit from Bruce Lines, the father of former Conservation Services summer intern Alex Lines.

“The Lines family had recently established a business in Hamilton and one morning Bruce happened to notice a snail in his shop that looked remarkably like the snails he helped Alex look for 12 years earlier, only much larger,” says Mr. Outerbridge. “This was an extraordinary moment for two reasons; not only was Bruce one of the few people on Bermuda at the time who knew what Poecilozonites looked like but he had also fortuitously moved into one of the last remaining refuges of the greater Bermuda land snail [a second subpopulation was later discovered in 2017 on an island in the Great Sound — by another summer intern!]

“It just so happened that a small but thriving colony was inhabiting a narrow, dank alley behind Bruce’s shop.”

The out-of-the-way location had kept the snails isolated from predators and allowed them to find a way to survive.

Following in the footsteps of Dr Sterrer, Mr. Outerbridge collected 166 snails from the alley and sent them to the London Zoo which had been running a captive breeding programme for lesser Bermuda land snails since the early 2000s. London Zoo subsequently shared specimens of the greater Bermuda land snails with the UK’s Chester Zoo, which began its own focussed effort to build up the population.

“Thankfully both the greater and lesser Bermuda land snails responded well to life in captivity and appeared quite content to live in climate controlled rooms eating fresh vegetables,” says Mr. Outerbridge. “The dedicated breeding efforts in the UK produced thousands of snails over the next four years which allowed for the repatriation and release of more than 18,000 greater Bermuda land snails on five different islands, all of them nature reserves, by 2019.

“These islands had suitable environments to support the snails and appeared to be free of the major predators.”

You can read more about the Department of Environment & Natural Resource’s recovery plan for the greater and lesser Bermuda land snails here.