One of the world’s rarest seabirds has successfully nested in Bermuda again after an absence of 169 years, the Bermuda Audubon Society has confirmed.

A single pair of Roseate Terns, Sterna dougallii, took up residence on a small posted nature reserve islet in the Hamilton Harbor/Great Sound area in June.

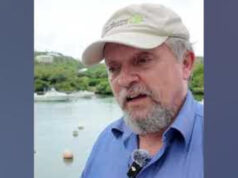

The Bermuda Audubon Society, which has been monitoring the birds, said they are pleased to report that the breeding was successful. A video camera mounted on the island by Audubon volunteer Erich Hetzel has obtained good documentary evidence of the nesting.

The Society explained, “The Roseate Tern, once common in Bermuda, last nested on remote Gurnet Rock at the entrance to Castle Harbor in the late 1840s, but was wiped out by scientific collectors and bird shooting “sportsmen” of the period.

“The Roseate pair were first spotted in Hamilton Harbour by David Wingate and Miguel Mejias on 22 May. In early July they were confirmed to be a breeding pair with an egg.

“Out of concern for the safety of the birds and the egg/chick, it was decided to keep the exciting news quiet until the chick had fledged,” said Dr David Wingate.

“The egg hatched on 24 July and the chick was double-banded and blood sampled for DNA. It has now fledged and will probably head south with its parents within the next couple of months to spend the winter off the east coast of Brazil.

“It is highly likely that the same pair will return to nest again next year, but the chick which we nick-named Phoenix, will take at least three years to mature.

“I want to thank Erich Hetzel, Miguel Mejias, Jo Smith and Lynn Thorne who assisted in watching out for the birds and carefully monitoring this extraordinary event.”

The Society noted that the “tragic extinction of Roseate Terns in Bermuda in the 1800s was documented in the natural history diary of John Hurdis and underscores how dramatically our attitudes towards conservation have evolved:

1 August 1847: “Saw Mr. Salton Smith…. and questioned him about a visit he kindly made at my request to the black rock [Gurnet Rock] near Castle Harbor in August. The sea was rougher than anticipated and he had some difficulty in landing a boy upon the rock. The boy twice returned with specimens of young seabirds consisting of about a dozen “redshanks” [terns]… He then went for eggs and returned with some dozens in the fold of his shirt; with these he attempted to jump into the frail little bark… but missed his footing, fell into the water and was in danger of being drowned. Mr. Smith, in his endeavor to save the boy, was carried on the rock, the dinghy was upset and stove, and the whole of the specimens and eggs lost”.

13 June 1848: “Mr Wedderburn visited the black rock. He found it tenanted by forty or fifty of the roseate tern of which he killed seven specimens.

2 June 1849: “Mr. McLeod … visited the black rock this day. He tells me he saw only 4 terns there, two of which he killed.”

21 June 1849: “Mr Orde and McLeod visited the black rock …. Of terns they saw none…..”

“Bermuda still has a small population of the Common Tern, Sterna hirundo, which was more fortunate than the Roseate Tern and managed to survive into the 21st century, but has seen numbers drastically reduced in the last two decades due to hurricanes hitting during nesting season,” the Bermuda Audubon Society said.

This population has been studied by the former Conservation officer, Dr David Wingate, over a 68 year period, with two scientific papers slated for publication in the near future.

“One encouraging fact about the Roseate Tern recolonization is that they are much better adapted than Common Terns to survive hurricanes, and largely replace the latter in the hurricane belt, notably in the Bahamas and the Antilles,” said Dr. Wingate.

“They were, in fact, much more common than the Common Tern on Bermuda before that 19th century massacre. So, when a single migrant Roseate Tern joined the Common Tern colony over the past two years and began courting with them it was a hopeful sign.

“This year that bird brought a mate of its own species with it and the rest is history. What a fitting culmination to a lifetime of work trying to conserve and restore these graceful additions to our summer scene.”